It’s been almost three weeks since I arrived in Rome and I haven’t posted anything here yet. It is true that I have been very busy, especially at the Anglican Centre, where I have helped Archbishop Ian Ernest and the whole team to organize the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. The fact that I was very busy, however, is not the only reason why I did not write. There is no shortage of things to write « home » about: the warm welcome I received from the rector of St. Paul’s, Father Austin and his wife Maleah; my first Sundays at St. Paul’s where I was able to meet some parishioners and participate in the service in English at 10:30 a.m., then in Spanish at noon; or even the many ecumenical meetings I had at the Anglican Centre where every Thursday morning a group of Methodists, Presbyterians, Catholics, Orthodox and of course Anglicans gather together to pray.

Yet in all of this, in this new place for me, in this new context, I felt the need to take time to listen and get to know “the spirit of the place” before writing anything.

For the ancient Romans, the genius loci (spirit of place) was an actual spiritual being that inhabited and protected a particular place. Private and public place had their genii. With the christianization of Roman culture, these spirits were also converted, their patronage being recognized as angelic protections, that of the Virgin Mary or of the saints. It gave rise to a very embodied and omnipresent popular piety which is very present in Rome (and even more so in southern Italy, I was told!)

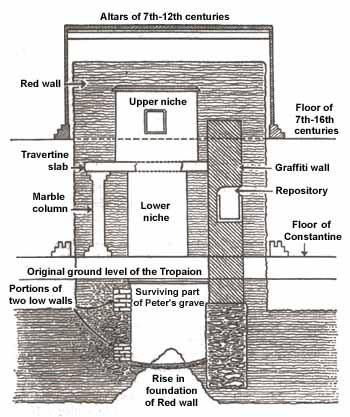

In Rome all churches are under the patronage of a saint (or several!) whose life and obedience to Christ brought the Christian community together. The first and most important of these churches is St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome built around the tomb of St. Peter on the Vatican Hill. I had the chance last week to visit the basement of the basilica with a group of pilgrims and American students from Nashotah House. What struck me during this visit is the way in which the sacredness of the whole church, that of the assembly and of each of the faithful who take part in the body of Christ derives in a very physical sense from the martyrdom of Peter. When Peter was tortured, crucified upside down during Nero’s persecutions of religious and political minorities, his body was buried in a simple tomb near where he was executed, on the Vatican hill (which was already a cemetery). In the years that followed, the Christians of Rome built him a mausoleum of the same type as the polytheistic mausoleums, called a « trophy », the remains of which can still be seen today. With Peter, the pagan « trophy » took on a new meaning, that of the victory over death acquired by Christ and in which each of us can take part. Emperor Constantine and then the popes built and rebuilt successive altars in the basilica just around and above Peter’s tomb, in a way that looks a bit like Russian dolls or the different layers of an onion.

So today when the Pope celebrates Mass at the high altar, he does so in the presence and continuity of the martyred and sanctified body of Peter, which is for everyone the sacrament of a life completely offered to Christ, like Christ himself offered himself completely for us. More than a spirit, it is the same body that brings the Church together, the body of Saint Peter which is itself part of the body of Christ who he followed until death.

The Episcopal Church of Saint Paul’s in Rome, having chosen as patron saint the apostle of non-Jews, (also martyred in Rome!) is part of this continuity. For us Christians the « spirit of place » that keeps us and makes us grow in the knowledge of ourselves and of God is an incarnate Spirit. It is he who engenders Christ and each of his disciples. The life of Christ, his death and resurrection and all the testimonies of the saints, transmitted by the Bible and by tradition, give us life in their wake. It is in the body of Christ that we are gathered and protected, in each Christian community that welcomes us, where we can find love, comfort, forgiveness.

The Bible readings of the past few weeks tell us about inhabiting a specific place and time. What does Jesus do during those hidden years that go from his early childhood to adulthood where his ministry began? What does he do from his twelfth to his thirtieth birthday? These years of Christ’s « hidden » life are, I believe, the years in which the God that he is grew in humanity: not only because he grew in strength and maturity but because he silently did the experience of our humanity, and of all his creation, his human family, and his town in Galilee. During his hidden life he communicated with the world which surrounded him unawares of who he was so that all the world could be welcomed in his Father’s fold.

Rome is full of the presence of Christ, visible and invisible, and I am happy to be able to live here for a while. When your heart fails you can just look up and see a Madonna around the corner or walk into a church. Places and encounters pray with you and invite you to pray all the time:

“Resisting the tendency to restrict prayer to set times, we are to aim at Eucharistic living that is responsive at all times and in all places to the divine presence. We should seek the gifts which help us to pray without ceasing. The Spirit offers us the gift of attentiveness by which we discern signs of God’s presence and action in creation, in other people, and in the fabric of ordinary existence.”

The Rule of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, “Prayer and Life,” Chapter 22.